The EU has announced that it will release EUR 10 million to fund research looking at the link between the mosquito-borne Zika virus, which is sweeping South America, and severe brain malformations seen in newborn babies, known as microcephaly.

The Zika virus spread from Polynesia to Brazil during 2014, and in January 2016 the World Health Organization (WHO) said it expected the virus would spread to most countries in the Americas.

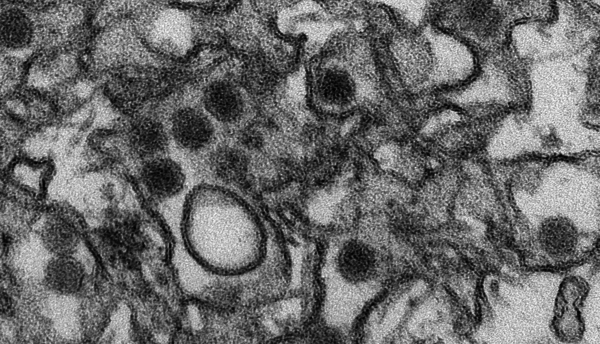

The vast majority of people who catch the disease feel no symptoms whatsoever. However, Zika infection in pregnant women has been linked to a rise in the number of children born with underdeveloped brains, a severe condition known as microcephaly, leading the WHO to declare it a public health emergency in February 2016.

“I think that now, the whole scientific community believes there is a link of cause and effect between Zika infection during pregnancy and microcephaly,” said Professor Jean-François Delfraissy, director of immunology, inflammation, infectious diseases and microbiology at INSERM, the French national institute for health and medical research.

“However, people aren’t in agreement over the significance of the link,” he said. “Some say around 1 % of (the babies of) pregnant women with Zika develop microcephaly, and others go as far as saying that it is around 20%.”

France, along with the EU, was one of the founding members of the global GloPID-R network. The network is an umbrella organisation which brings together national responses to urgent emerging worldwide disease threats and is now helping to coordinate work on Zika.

At the moment, researchers are tracking pregnant women in Martinique, Guadeloupe and Guyana in order to find out what percentage of their babies end up with microcephaly. However, as well as understanding the risk of microcephaly, the priority for research is to monitor the virus in case of any mutations, although none have been seen yet.

“We have sequenced a very high number of viruses, the Americans have done it too,’ said Prof. Delfraissy. “The virus is the same as the one we saw in Polynesia two years ago, exactly the same.”

The EU has stepped in quickly to tackle Zika, but the next thing should be for Member States to also support Zika research, according to Prof. Delfraissy.

“Europe has reacted very effectively, now we have to think that Member States can also help finance research into Zika,” he said.

The funds from the EU might also be used to help with find ways to combat the virus, it said in a statement, which would include developing diagnostics and testing potential treatments or vaccines, once the link with microcephaly has been understood well enough.

Despite ongoing trials on using genetically modified mosquitoes who cannot reproduce in order to cut back on the number of insects that carry the disease, Prof. Delfraissy believes there’s no stopping the virus.

“I don’t think we can do much to prevent the extension of the epidemic,” he said. “For the moment, as regards preventative measures against mosquitoes, there aren’t really any measures that have proven their effectiveness.”

It means the likelihood is that there will be some cases in Europe when the weather warms up enough for mosquitoes to survive, he said, although he believes it isn’t likely to become a pandemic due to hygiene standards in Europe.

On top of that, there’s also evidence of direct human-to-human sexual transmission, although Prof. Delfraissy does not think this will become the main transmission route in the Americas or in Europe.

“We think it’s a relatively marginal phenomenon,” Prof. Delfraissy said. “However, I can’t say for sure today, I don’t have enough data. It’s a risk, the level of this risk we don’t know.”